A recent project about traditional dress in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) got us thinking about good old Roland Barthes. He famously interpreted fashion as a language, which, like all languages, is full of myths, codes and paradoxes; at once superficial and profound; fixed in some ways, evolving in others; always subject to personal interpretation, collective judgement and commercial exploitation. The subject is a fascinating one and Barthes published two books on it: The Fashion System (1967) and The Language of Fashion (2006).

While Barthes wrote about linguistic and industrial aspects of French fashion, we explored the unique nuances of clothing in this part of the world. As a team of non-Arab expat journalists, it was exciting to learn about the sartorial traditions in the Arab Gulf countries, with a special focus on the UAE.

As always, our Arab and Emirati colleagues supported the project with first-hand input and, in this case, even practical demonstrations:

Meaningful monochrome

Garments take on a heightened significance in traditional societies such as the UAE, where the majority of locals wear national dress every day, although this is a relatively recent custom. UAE national dress as we see it today only dates back to the 1970s, when the Islamic Revival, which brought a resurgence of Muslim religion and traditions, gained momentum. In the realm of fashion, this chiefly meant a return to modest, plain clothing coupled with a general rejection of Westernisation and commercialisation. At the time, many people in the UAE wore Western clothes or a mixture of Arab and Western attire, so the Islamic Revival created a new fashion mainstream, which not only manifested the country’s religious and cultural values, but also clearly distinguished nationals from expatriates. In a country where more than 80 per cent of the population consists of expatriates, Emiratis have come to use national dress as a way to differentiate themselves from the majority of ‘others’ and to express pride in their native culture.

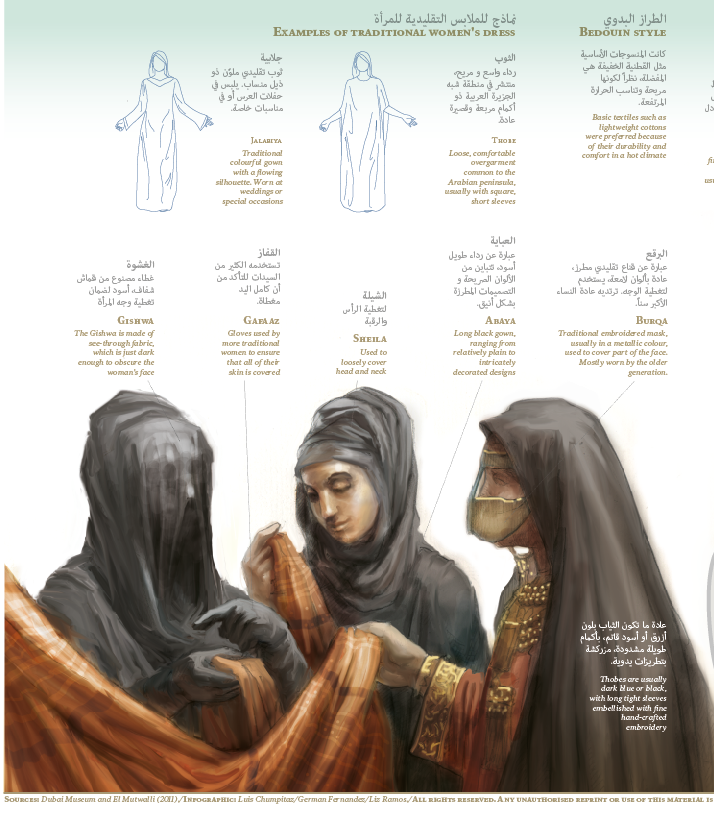

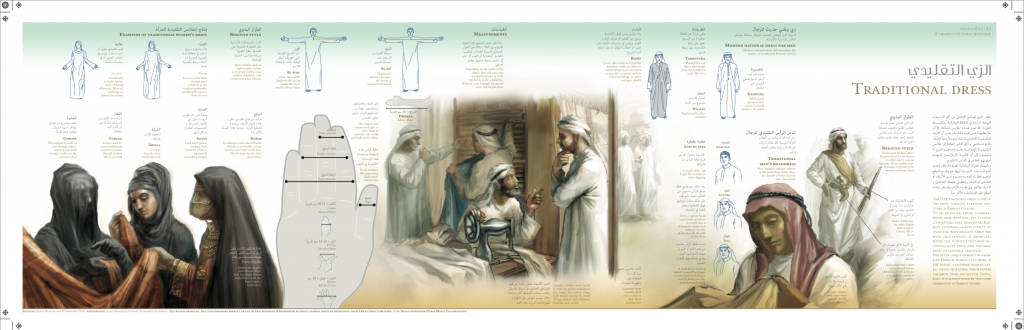

Compared to traditional clothing worn in other parts of the world, it is striking how demure and uniform the sartorial cultures of the Gulf countries are. As shown in the infographic, Khaleeji (Gulf Arab) national dress commonly consists of a loose-fitting black cloak (Abaya) worn with a black headscarf for women…

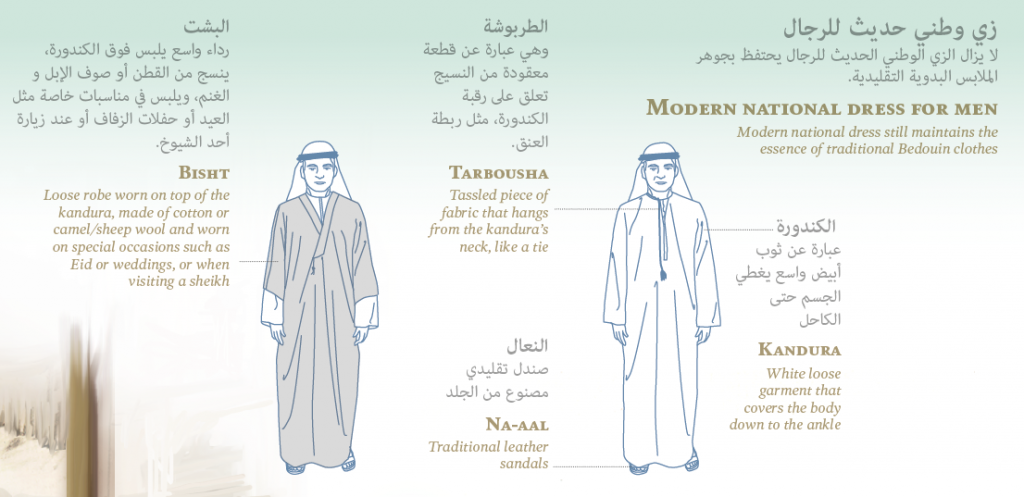

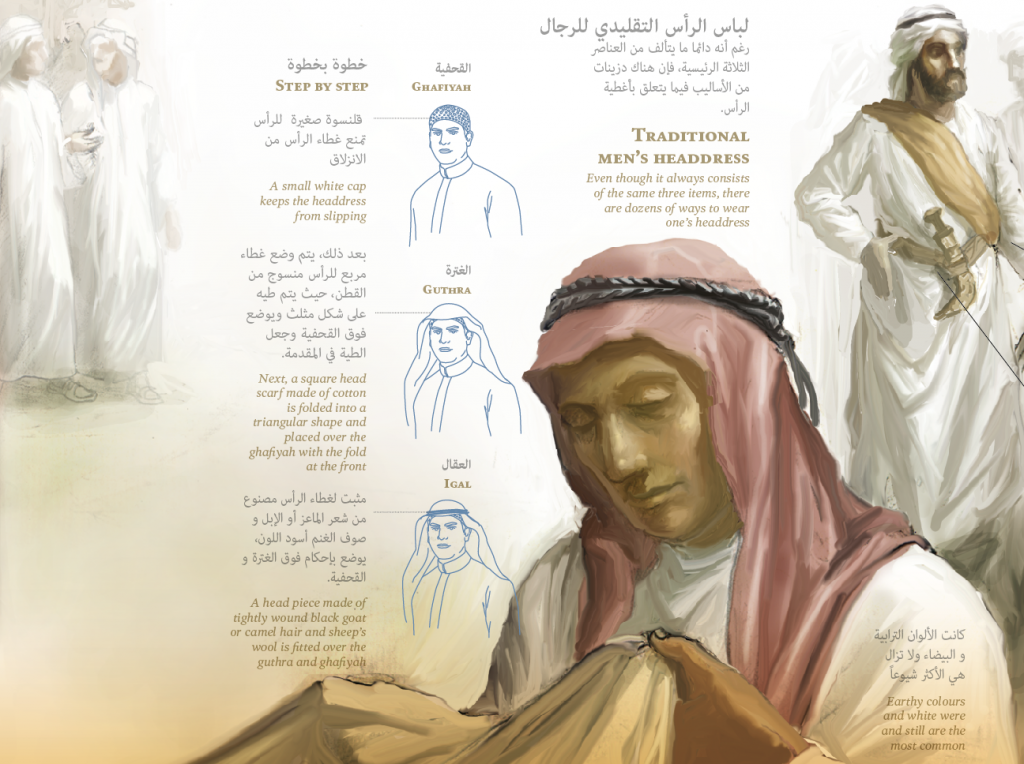

… and a white ankle-length garment (Kandura) worn with a white or red-and-white headscarf for men.Whether in Kuwait City, Doha or Dubai, the colours worn in public are mostly monochrome, punctuated by the occasional, usually male, wearer of brown, grey or patterned materials.

Had we done an infographic about traditional dress almost anywhere else in the world, the colour palette would have looked quite different. Especially if you consider the colourful traditional clothes worn in such disparate places as India, Peru and Vietnam:

Elsewhere, traditional costume may be more overtly expressive and signal social hierarchy (the more ornate, colourful and exquisite the outfit, the higher the status of the person who wears it) or geographical roots in an instant. In the UAE, the signals of social rank and regional origin are also there, but more subtle. Brand names are often discreetly stitched into the hem of an Abaya or the cuff of a Kandura, while regional origin is conveyed through comparatively light variations in headwear, collars and other details easily overlooked by an outsider. Once you are attuned to it, however, you quickly realise that what at first seems like a homogenous dress code, is actually full of variation.

This is because traditional dress in the UAE continues to evolve, albeit slowly. The market for traditional designer clothing is booming and big-brand accessories are all the rage. One could easily get the impression that European and American designer shoes, bags, sunglasses, jewellery and watches are the norm rather than the exception. Today, what a typical Emirati wears is subject to a complex, often contradictory interplay between customs, commerce and individuality.

New is the new black

Although Barthes didn’t write about traditional costume or the Arab world, some of his concepts do resonate in the UAE. For example, Barthes was especially interested in the way the fashion industry, of which the French fashion magazines he studied were a key part, entices people to continually buy new clothes. “Calculating, industrial society is obliged to form consumers who don’t calculate; if clothing’s producers and consumers had the same consciousness, clothing would be bought (and produced) only at the very slow rate of its dilapidation,” he wrote.

As unusual as the UAE’s traditional clothing culture may be, newness is one aspect it shares with global fashion and with the fashion industry as written about by Barthes. People do not wear clothes out. New garments are bought all the time, usually not on the basis of need, but because of the desires and subtexts created by the fashion industry. “The New is not a fashion, it is a value,” wrote Barthes. This famous quote from The Fashion System applies in Dubai and Riyadh as much as it does in Paris and Shanghai; to an Abaya as much as to a little black dress.

About this infographic

After much experimentation, we ended up with a series of almost cinematic scenes, around which we arranged a stream of information, flowing from right to left, past to present, menswear to women’s wear. As in most of our infographics, Arabic and English text is presented side-by-side on the page. An earthy colour palette and classical style suited the project’s historico-anthropological theme. On the right, we decided to show attire that is no longer worn, such as a Bedouin brandishing a rifle and dagger, as was customary in the UAE during colonial times.

This project was realised over a period of about four weeks in late 2011. It was quite a challenge, but in the end it did come together. In 2012, it was even recognised with an award of excellence from the Society of News Design. As they say, all’s well that ends well.

Pingback: Data Viz News [12] | Visual Loop