A city like Dubai, home to people from around 200 different countries AND the world’s highest skyscraper, readily lends itself to analogies with the story of the Tower of Babel. Any given day, you are interacting with people who speak a dozen different languages, trying to make yourself understood and to understand others. In a scenario like this, the ideals of universal languages like Esperanto take on a special allure. As infographists and visual journalists, we can’t help asking ourselves: what if we could create a visual Esperanto? Would it even be possible and what would it look like?

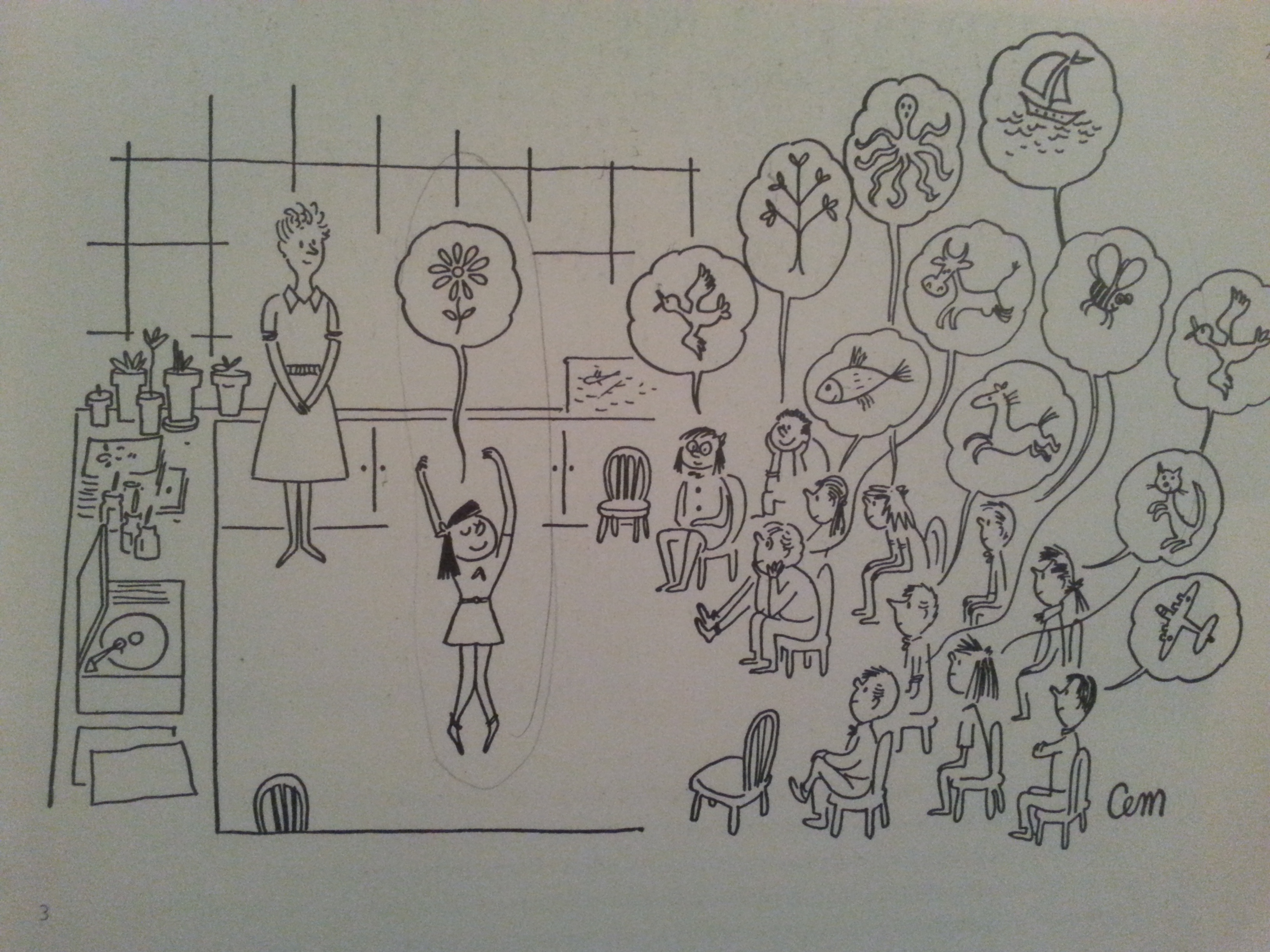

The picture above, from Paul Mijksenaar’s seminal book Open Here: The Art Of Instructional Design nicely sums up the dilemma faced by all language systems, whether they are oral, written or visual: when a group of people receives a message, each individual will derive his/her own meaning from it. Messages are decoded and meaning established based on a person’s background and cognitive habits. Signification is never fixed, but dependent on the audience’s collective and individual culture and worldview.

This post, the first of two on the subject of universal communications, looks at the evolution of auxiliary languages in the past and how they could relate to the world of infographics. Part two will explore the rise of visual culture and past attempts to create universal languages based on images.

Languages are a thing of beauty, but their sheer variety is daunting and, at times, problematic. Separated not just by differing vocabulary and grammar, but also by different scripts and orientations, they come fully loaded with inherent symbolism, values, emotions, faith and politics. But it is essential to look at the need for and possibility of universal languages in pragmatic terms. Obviously, unlike in biblical Babel, the multitude of languages we have today is no punishment. In most places, the existence of many languages in a single place is the hallmark of complex, progressive societies marked by vibrancy and tolerance, although occasionally also by confusion and friction.

The same could be said of the world of infographics. When it comes to the visualisation of information, there innumerable viewpoints and practices, each based on different systems of signification and diverging notions of reality and abstraction, form and function, ideal and compromise. Finding common ground is far from easy, since infographics, like verbal language, mirror the diverse cultures and societies they emerge from. Early initiatives to create verbal languages that could be easily learned and understood by people from all over the world paved the way for more recent attempts of creating universal visual or graphical languages (more on this in part two).

A short history of auxiliary languages

The formulation of universal languages has always been a difficult affair; a fascination shared by philosophers and scientists, politicians, statisticians and, more recently, visual journalists.

In the 17th century, German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz (pictured left) imagined the “characteristica universalis”, a universal language of science, an alphabet of human thought. But Leibniz’ initial enthusiasm for the idea faded as challenges mounted and interest dwindled.

In the 19th century, Gottlob Frege (pictured right) introduced the idea of “conceptual writing”, which promoted the optimised use of both dimensions of the writing space (left to right, top to bottom). Although fascinating, his ideas had equally little impact on international communications.

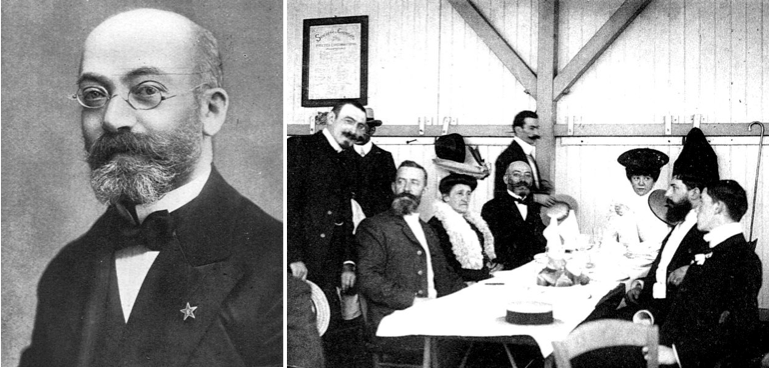

It was not until 1887 that a Polish doctor and linguist named L. L. Zamenhof (pictured below) launched the most successful auxiliary language to date: Esperanto. Rooted in Romanic, Slavonic and Germanic languages, Esperanto’s simple structure and egalitarian values have created a global community of hundreds of thousands of people. “Communication through Esperanto does not give advantages to members of any particular people of culture, but provides an ethos of equality of rights, tolerance and true internationalism, ” according to Tutmonda Esperantista Junulara Organizo, the Esperanto youth movement.

So could a language system comparable to Esperanto be established for visual communications? Watch out for the second part of this post, which will look at the people and ideas behind key initiatives to develop such a visual lingua franca.